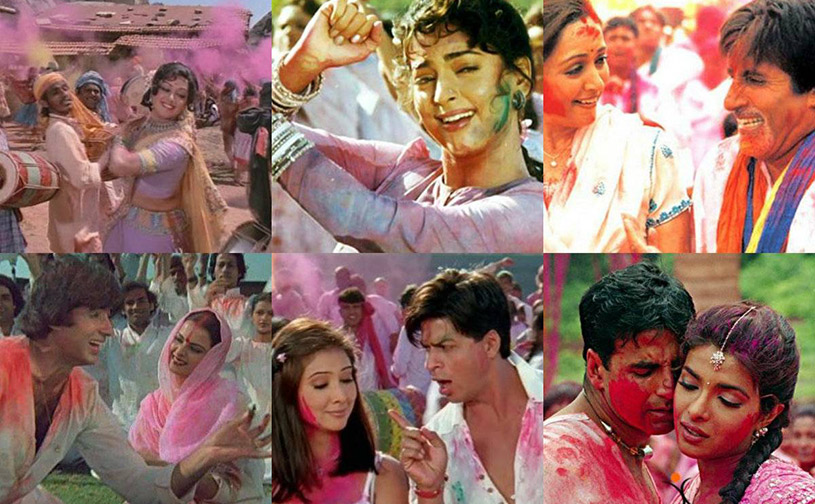

Holi/Phagwa Celebration by Indranie Deyal

|

|

| Holi/Phagwa Celebration by Indranie Deyal | |

| Packets of vivid powders would lie on the formica kitchen table like scattered pieces pulled from a pretty patchwork quilt. Bags of iridescent green crystals glittered in the morning sunlight and bottles of scented white talcum emerged from my mother’s sturdy vine-woven market basket in preparation for the annual Hindu festival of Phagwah or Holi.

A riot of colors that signifies the start of spring, the celebration of Phagwah during the Hindu month Phalgun came with the immigrants who left Bhojpur and other parts of India for the tropical West Indies in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Phaguwa in the distinct Bhojpuri dialect still survives as the original name of the national holiday in Guyana, while Holi is derived from the Hindi. |

|

|

My mother, born nearly a century ago, was continuing an ancient custom, brought by her parents to their uncertain new world. These traditions had their deep roots in an agrarian society where the end of winter signalled the start of new life and renewed fertility, and reinforced the belief in a natural order and constant cycle that were reassuring and reaffirming in their predictability, while comforting for the classic message of justice and good overcoming evil. Excited, I would peer into her brown carrier to admire all the ingredients for the sweets and savouries that would be prepared for the two day observance, which really blazed on the night of the full moon, Phalgun Purnima, when huge bonfires would illuminate the villages including the area in South Georgetown where we lived. We grew up hearing, then reading, about the legend of the young Prince Prahalad who defied his megalomaniac father to worship Lord Vishnu. Thousands of years old, the much-loved story tells of the King Hiranyakashipu who is granted a special boon by the Creator Brahma. |

| Conferring five special powers, the gift stipulates that the ruler cannot be killed by a human being or an animal; by astra (projectile weapons) or by any shastra (handheld weapons); on land, in water or air; indoors or outdoors; during the day or at night. | |

|

|

|

Feeling understandably invincible, Hiranyakashyapu becomes arrogant and decrees that only he could be worshipped as a God, so when his son defies him, the enraged king orders his sister Holika who wears an inflammable cloak to trick the prince to sit on her lap in a raging conflagration. But the garment flies off Holika and covers Prahalad who escapes while she dies The countless pieces of dried wood, twigs, branches and the symbolic castor oil tree planted on Basant Panchami 40 days before, perhaps testimony to the purgative powers of the fruit, would be consumed in the Holika Dahan or the great cleansing fire, crackling under the silver moon, the embers and smoke reaching far into the sky. According to the Puranas or the old, sacred Sanskrit writings, the outraged Lord Vishnu, ingeniously gets around Hiranyakashyapu’s apparent immortality by appearing in the form of Narasimha, or a being that is half human and half lion, at dusk, on a doorstep, and seizing the tyrant in his lap, killing the king with his claws. |

|

|

We would stare in grim fascination at the pictures, gripped by the tale. That night we would listen and sing to the rousing Phagwah songs or off-colour chowtals and Bhojpuri gana music loved by families, arrange our own prayers and little bonfire or travel further into Georgetown or further afield for the ceremonial puja and huge blaze organized by the various Hindu Sabhas.

The mothers of the neighborhood would prepare huge pots of boiling water to dissolve and dilute the fine gleaming crystals of potassium permanganate to create the hallmark magenta hues or “abeer” favoured by most revellers, so that it would cool by morning to pour from buckets and spray from our plastic bottles. A strong oxidizing agent, the salt of manganese and potassium, chemical formula KMnO4 is a cheap antiseptic used for cleaning wounds and dermatitis. When the “abeer” ran out, we resorted to soaking each other with buckets of plain water, wisely wearing old clothes or the preferred white cotton when we could afford it, proudly showing off our stained hands and faces to see whose was the darkest. |

| One oliday, my sister had the bright idea of soaking a pair of her faded corduroy jeans in the container of the remaining mix, added salt to prevent it running and she wore those intense fuchsia trousers until the cloth tore!

The afternoon was reserved for the “dry” half of Holi, white talcum from a “My Fair Lady” tin or a Johnson’s container sprinkled liberally on the hair and faces. The brilliant range of powders called “abrack” or “gulaal” my mother purchased to reflect the beautiful hues of the season would follow. Thinking back, these must have been synthetic, or coloured with food dye, dried and packaged into their little ribbons of plastic. We lacked the plant-based ingredients except turmeric, used to tint the powders and liquids, ranging from the red of the palash or flame of the forest trees to fragrant sandalwood, madder, radish, pomegranate, henna, indigo and beetroot. Anyone was game, and in my multiracial community everyone took part. Some resorted to the dreaded ashes and mud dissolved in water, others drove with their car windows wound tightly up, and quite a few poor souls on their way to church on the Sunday that Phagwah occasionally came, fell angry, wet victims and had to turn back home. |

|

|

|

Remaining a fiesta for the senses, Phagwah is of course also an occasion for feasting, but in our homes, the practice remains strictly vegetarian and non-alcoholic, paying tribute to the earth’s bounty of fruits, greens and crops harvested locally. My mother was famous for her creamy kheer, “gojhas” – fragrant, filling pastries stuffed with sweetened grated coconut and “gulgulahs” – deep fried spongy fruit balls made from soft, kneaded dough packed with crushed sweet fig or what Trinis call “sucrier” or “chiquito” bananas. Today we also create smooth milky “perahs or pedahs”, dripping gulaab jamuns, barfi, rasgullah and rasmillai, besides the usual mohanbog, sawine and methai, plus the all-time popular savouries of pholourie, baiganee or crispy sliced eggplant in a seasoned split pea batter, kachowrie, sal sev (humourously dubbed ‘chicken foot’), bara etc. My mother was famous for her creamy kheer, “gojhas” – fragrant, filling pastries stuffed with sweetened grated coconut and “gulgulahs” – deep fried spongy fruit balls made from soft, kneaded dough packed with crushed sweet fig or what Trinis call “sucrier” or “chiquito” bananas. Today we also create smooth milky “perahs or pedahs”, dripping gulaab jamuns, barfi, rasgullah and rasmillai, besides the usual mohanbog, sawine and methai, plus the all-time popular savouries of pholourie, baiganee or crispy sliced eggplant in a seasoned split pea batter, kachowrie, sal sev (humourously dubbed ‘chicken foot’), bara etc.

For some Hindus, Holi marks the beginning of a fresh crop and a new year, and an auspicious opportunity to forgive, to heal and to start again in the perpetual struggle to triumph, whether over one’s baser self or the ongoing challenges in a turbulent time. Given the speed at which our worlds are changing, whether families or villages, communities or countries, it is fitting that the commemoration continues, the rites remain, and Phagwah prevails. Indranie Deyal is red from hearing of unholy music events – such as the Festival of Colours Tour and Holi One which feature timed throws of powder – plus marathon franchises like Holi Run and Color Me Rad in which runners are doused at regular checkpoints. |

|