Passing the Torch to the Next Generation

Family, Food, Festivals, and the Indian Values That Endure

By Raj Shah

When our children look back, what will they remember—our success or our values? As Indian Americans, we have much to acknowledge with quiet pride. In just a few decades, a community that arrived with limited resources has built lives of stability and opportunity.

We have educated our children, entered respected professions, created thriving businesses, contributed to innovation, and earned recognition in a country far from where many of us began.

These achievements do matter. They reflect sacrifice, resilience, and perseverance. Yet success, by its nature, remains external. It is visible, measurable, and easily celebrated.

The deeper question, however, calls us inward. It asks not only what we have achieved, but what we are carrying forward—what values, traditions, and ways of life will endure when success alone is no longer the measure.

What Are We Really Passing On?

What, beyond material comfort and professional success, are we passing on to the next generation?

This question is not philosophical alone. It is deeply practical. “Wealth can be transferred. Education can be planned. Careers can be guided. But culture, values, and identity do not pass automatically.” They require presence, intention, and everyday living. They are transmitted not through speeches or institutions, but through homes—through shared meals, conversations, rituals, celebrations, and relationships.

The torch I speak of in this issue of Desh-Videsh magazine is not ideological. It is not about leadership positions or public recognition. It is far more intimate. It is the quiet inheritance of how families live, what they honor, and what they choose to preserve when no one is watching. It is the way elders are spoken to, the way guests are welcomed, the way gratitude is expressed, the way festivals are observed, and the way faith is practiced—or not practiced—within the walls of a home.

In January of Desh-Videsh I talked about “The Rise and Rise of Indian Americans.” The narrative of rise and recognition is important. It tells us how far we have come. In this issue of Desh-Videsh magazine, I want to talk about an equally important aspect of our rise: culture and heritage. A community can rise economically and still lose its cultural focus. Therefore, our focus should not be ONLY on our achievements but rather on the foundation of our success.

“In America, culture rarely disappears through rejection. It fades through neglect.” It slips away in the rush of daily life, in the belief that there will be time later, and in the assumption that children will absorb identity simply by being born into it. Yet identity does not survive on intention alone. What is not lived is eventually forgotten.

“Passing the torch does not require grand gestures. It begins quietly, at home.” It begins with the decision to prioritize presence over pressure. In valuing connection over convenience. In recognizing that what we pass on today—intentionally or unintentionally—will shape how the next generation understands who they are long after the applause fades.

The Family serves as the First Cultural Classroom.

Culture is not first learned through books, weekend classes, or formal instruction. It is absorbed quietly, long before children have the language to describe it. The family home is the first and most influential cultural classroom, and parents are its most powerful teachers—not by what they explain, but by what they live.

Culture is not first learned through books, weekend classes, or formal instruction. It is absorbed quietly, long before children have the language to describe it. The family home is the first and most influential cultural classroom, and parents are its most powerful teachers—not by what they explain, but by what they live.

In Hindu tradition, sanskar was never a lesson plan. It was not delivered through lectures or enforced through rules. It was transmitted through observation. Children learned by watching how elders spoke to one another, how guests were welcomed, how disagreements were handled, and how daily life unfolded. Values were not discussed abstractly; they were demonstrated repeatedly.

Respect for elders, for example, was not taught as a concept. It was practiced. Children observed how parents addressed grandparents, how decisions were discussed, and how patience and deference were shown. Over time, respect became instinctive rather than imposed. In many Indian American homes today, this transmission is challenged not by lack of intent, but by lack of exposure. When extended family is distant or daily interactions are rushed, children have fewer opportunities to witness these relationships in action.

Shared meals once served as natural gathering points for family life. They were moments when stories were exchanged, values were reinforced, and bonds were strengthened without effort. Today, meals are often fragmented—eaten at different times, in different spaces, or in front of screens. What is lost is not merely conversation, but continuity. A child who rarely experiences family meals loses one of the most powerful settings for cultural learning.

Daily routines, though seemingly mundane, shape identity more deeply than occasional events. Morning greetings, bedtime rituals, simple prayers, household responsibilities—these repeated actions communicate what a family values. They create rhythm and familiarity. Children do not need constant explanations to understand that something matters; they sense it through repetition.

One of the most overlooked truths of cultural transmission is that children learn identity long before they consciously understand it. They absorb tone, behavior, and priorities emotionally before they can articulate meaning intellectually. By the time questions arise—about faith, culture, or belonging—the foundation has often already been laid.

This is why consistency matters more than intensity. Culture that passes sporadically or only on special occasions struggles to take root. Culture lives gently but regularly becomes part of a child’s inner world. Even imperfect consistency—shared meals a few times a week, simple rituals observed occasionally, respectful interactions modeled daily—has a lasting impact.

The family as a cultural classroom does not require perfection, structure, or expertise. It requires presence. When children grow up seeing culture lived naturally at home, they carry it forward not as an obligation, but as a part of who they are.

Food as Memory, Culture, and Belonging

Long after specific lessons fade, taste remains. Food has a unique ability to anchor memory, emotion, and identity in ways that words often cannot. For many children, especially those growing up between cultures, food becomes the most enduring and instinctive connection to their heritage.

Long after specific lessons fade, taste remains. Food has a unique ability to anchor memory, emotion, and identity in ways that words often cannot. For many children, especially those growing up between cultures, food becomes the most enduring and instinctive connection to their heritage.

In Indian families, the kitchen has traditionally been more than a functional space. It is a cultural center—a place where generations meet, where stories are exchanged, and where identity is passed on quietly. The sounds, aromas, and rhythms of cooking form a backdrop to family life. Children absorb culture here without instruction, simply by being present.

Festival foods carry layers of meaning that rarely need explanation. A particular sweet prepared for Diwali, a savory dish made during Navratri, or a special offering during Janmashtami becomes part of a child’s internal calendar. These foods mark time. They signal celebration, reflection, and togetherness. Even when children do not fully understand the religious or historical significance, they remember the feeling associated with those moments.

Regional dishes deepen this connection further. They root children not only in a broad Indian identity but also in a specific place, language, and lineage. A Gujarati thali, a South Indian breakfast, a Punjabi winter dish, or a Bengali sweet carries with it the geography and history of a family’s origin. Family recipes, passed down through generations, act as edible archives—holding memories of grandparents, childhood homes, and shared experiences.

Children often remember taste longer than teachings because food engages the senses fully. It is experiential rather than abstract. While explanations can be forgotten or resisted, the sensory memory of a dish—its aroma, texture, and flavor—stays embedded. Years later, a familiar taste can evoke belonging more powerfully than words ever could.

In the American context, food sometimes becomes the last remaining cultural thread when other practices weaken. Language may fade. Rituals may become occasional. But the desire for familiar flavors often persists into adulthood. Such a desire is not nostalgia alone; it is emotional continuity. Food provides comfort, familiarity, and grounding in moments of stress or transition.

When families cook together, even occasionally, food becomes a shared language. Children who help prepare meals feel ownership rather than obligation. They learn culture through participation, not pressure. Allowing children to adapt recipes or blend traditions reflects the natural evolution of culture rather than its loss.

Food, at its best, is not a backward-looking reminder of what once was. It is a living expression of belonging. In passing down recipes and food rituals, families are not clinging to the past—they are nourishing continuity, one meal at a time.

Festivals: Joy Before Instruction

For children, festivals are not first understood—they are felt. Long before they can explain why a diya is lit or why colors are thrown, they absorb the excitement, warmth, and togetherness that surround these moments. This emotional experience, not intellectual explanation, is what allows festivals to take root in a child’s memory.

Indian American homes often celebrate festivals like Diwali, Holi, Navratri, and Janmashtami across two worlds. They exist within the rhythms of American life—school schedules, work commitments, neighborhood norms—yet carry traditions shaped over centuries. The way we experience these festivals at home shapes whether they become enduring memories or fleeting events.

Diwali celebrated quietly at home—lighting lamps together, preparing a special meal, sharing stories—often leaves a deeper impression than elaborate gatherings alone. Holi becomes meaningful when it is playful and spontaneous rather than staged for photographs. When kids hear stories informally before bed or witness adults joyfully participate, Janmashtami comes to life. Navratri gains significance when children observe devotion expressed naturally, not formally enforced.

Festivals lose power when they become performances. When children feel evaluated on whether they “know enough” or “do it correctly,” participation turns into pressure. Culture then feels like a test rather than an invitation. In contrast, festivals that emphasize joy, participation, and family connection create emotional attachment. Meaning follows naturally when curiosity is allowed to develop.

In the American context, temples and community centers play an important role in preserving tradition. Large celebrations offer scale, visibility, and collective energy. They help children see that their culture is shared by many. But temple celebrations alone cannot carry the full weight of cultural transmission. Without reinforcement at home, festivals risk becoming external events rather than internal experiences.

The home offers something temples cannot: intimacy. It is where children observe how culture fits into daily life. A small prayer before lighting a diya, a story told at the dinner table, a family conversation about why a festival matters—these moments personalize tradition. They allow children to see culture not as something performed occasionally, but as something lived.

Creating meaning without pressure requires restraint. It means resisting the urge to explain everything immediately. “Children do not need full understanding to belong.” Familiarity comes first. Questions arise later, when children feel safe and curious rather than obligated.

Festivals endure when they are associated with warmth, laughter, and connection. When joy comes first, meaning follows naturally. Passing festivals on in this way ensures they remain sources of comfort and belonging—long after the decorations are put away.

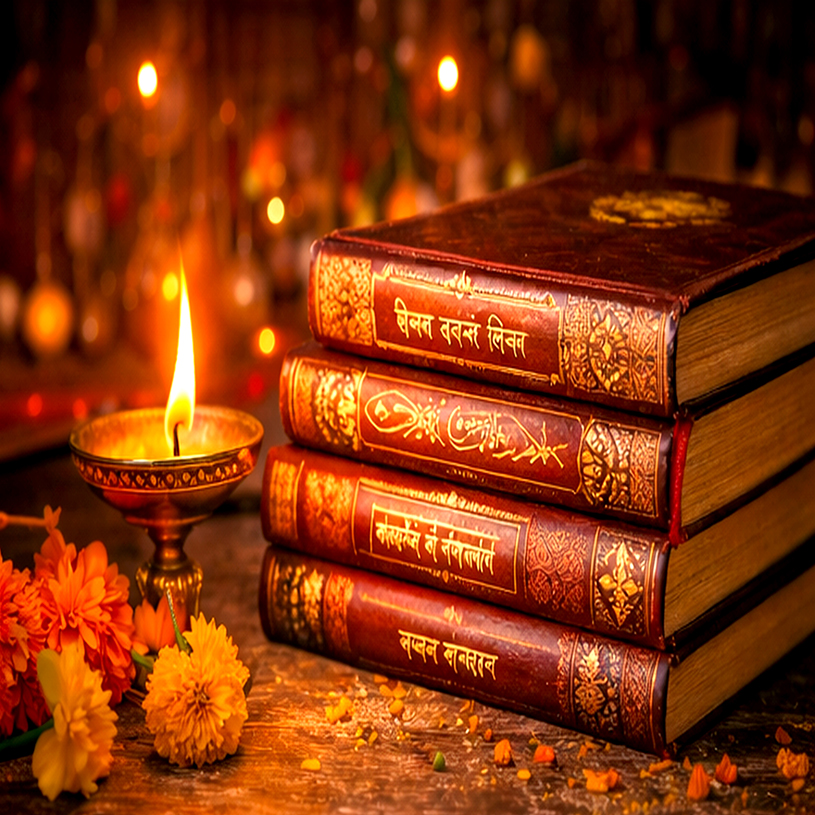

Everyday Hinduism: Faith Lived Gently

For many Hindu families in America, the challenge is not whether faith matters, but how it is expressed. Between the desire to preserve tradition and the fear of imposing belief, parents often struggle to find the right balance. Yet Hinduism, by its very nature, was never meant to be enforced. It thrives when it is lived gently and experienced naturally.

For many Hindu families in America, the challenge is not whether faith matters, but how it is expressed. Between the desire to preserve tradition and the fear of imposing belief, parents often struggle to find the right balance. Yet Hinduism, by its very nature, was never meant to be enforced. It thrives when it is lived gently and experienced naturally.

Simple practices often carry the deepest impact. A brief prayer in the morning, lighting a lamp in the evening, placing flowers before an image, or telling a story from the epics at bedtime creates familiarity without pressure. These moments do not demand belief or understanding. They offer presence. Over time, familiarity becomes comfort, and comfort becomes connection.

Hinduism has always provided rhythm to daily life. Its rituals mark beginnings and endings, transitions and pauses. In a fast-paced American environment, this rhythm offers grounding. For children navigating academic pressure, social expectations, and constant stimulation, small moments of stillness—folded hands, quiet reflection, familiar chants—can become sources of calm rather than obligation.

Allowing children to experience faith before explaining it is essential. Intellectual understanding is not the entry point for spiritual connection. Children absorb tone and emotion long before they grasp meaning. When faith is introduced through experience—through sound, gesture, and routine—it feels safe and familiar. Questions emerge naturally when children feel secure, not when they feel tested.

Forced religiosity, however well-intentioned, often produces the opposite effect. When children are required to perform rituals without emotional context or personal agency, faith becomes associated with pressure. The result can lead to resistance, avoidance, or rejection later in life. Many adults who drift away from religion do so not because they were exposed to it, but because they were overexposed without choice.

Some parents respond by removing faith entirely from home life, believing neutrality will allow children to choose later. Yet absence leaves a void. Children raised without exposure often grow curious but disconnected, unsure how to relate to traditions they never experienced.

Hinduism offers a wide, inclusive framework—one that accommodates inquiry, adaptation, and personal interpretation. When children see faith practiced sincerely but without rigidity, they learn that spirituality is not about perfection but about presence.

Faith that is lived gently does not demand adherence. It offers invitation. It creates an emotional anchor that children can return to at different stages of life. By passing on Hinduism in this way, families do not enforce belief; instead, they preserve a sense of belonging.

When the Roots Begin to Fade

Cultural loss rarely announces itself. It does not usually arrive through rebellion or rejection. More often, it unfolds quietly—through distance, distraction, and gradual disengagement. In many Indian American families, this drift goes unnoticed until much later, when parents realize that something once assumed has slowly slipped away.

Cultural loss rarely announces itself. It does not usually arrive through rebellion or rejection. More often, it unfolds quietly—through distance, distraction, and gradual disengagement. In many Indian American families, this drift goes unnoticed until much later, when parents realize that something once assumed has slowly slipped away.

Cultural drift is not about children refusing their heritage. It is about growing up without enough exposure to form emotional attachment. Many Indian and Hindu children raised in the United States do not actively reject their culture; they simply never fully inhabit it.

Some grow up without language. Without hearing their parents’ mother tongue spoken regularly at home, they lose access to humor, emotion, and family history embedded in words. Conversations with grandparents become limited. Stories are shortened. Over time, the emotional depth carried by language fades.

Others grow up without ritual familiarity. They may attend temple occasionally or participate in festivals sporadically but lack comfort with everyday practices. Rituals feel foreign rather than familiar. Without repetition, even simple acts—lighting a lamp, offering a prayer, participating in a ceremony—can feel awkward or intimidating.

Perhaps most critically, many grow up without emotional attachment to their cultural traditions. Culture becomes something external—observed but not owned. Without memories tied to warmth, joy, or connection, traditions feel abstract. When culture lacks emotional grounding, it is easily set aside.

This is why many second-generation youth describe feeling “culturally blank.” They feel somewhat connected to their parents’ heritage. They may feel unsure how to explain their background, hesitant to participate in cultural spaces, or uncomfortable navigating expectations from either side.

Educators, counselors, and community leaders increasingly observe this pattern. Many estimate that a significant portion of Indian American youth lose meaningful connection to their cultural roots by early adulthood—not through rejection, but through gradual disengagement.

This reality is difficult to confront, especially for parents who worked hard to create stable, opportunity-rich lives for their children. Yet recognizing cultural drift is not an admission of failure. It is an opportunity for awareness.

Culture is not lost all at once. It fades when it is postponed, outsourced, or treated as optional background rather than lived experience. But what fades quietly can often be revived gently.

Reconnection does not require drastic measures. It begins with small, intentional acts—shared meals, familiar sounds, casual stories, simple rituals, and genuine presence. Culture returns when it is reintroduced as belonging, not obligation.

Understanding cultural drift with empathy allows families to respond without blame. The goal is not to reverse time but to create meaningful connections moving forward—before the roots disappear entirely.

Why Identity Is Lost—Without Anyone Noticing

Identity is rarely lost through a single decision. It erodes gradually, shaped by the rhythms and pressures of everyday life. In Indian American families, this process often unfolds quietly, not because parents do not care, but because life moves quickly and intentions are repeatedly postponed.

Identity is rarely lost through a single decision. It erodes gradually, shaped by the rhythms and pressures of everyday life. In Indian American families, this process often unfolds quietly, not because parents do not care, but because life moves quickly and intentions are repeatedly postponed.

Busy lives often cause culture to fade into the background. Long work hours, academic demands, extracurricular activities, and the constant pull of screens leave little space for reflection or tradition. Convenience culture rewards efficiency over presence. Meals are shortened or separated. Conversations are rushed. Rituals are delayed for “another time.” Over time, what is delayed too often simply disappears.

Many families also outsource cultural transmission, believing that weekend schools, language classes, temples, or cultural organizations can carry the responsibility alone. These institutions play an important role, but they cannot replace daily exposure. Culture cannot survive on scheduled programming alone. Without reinforcement at home, what children learn in structured settings often remains theoretical—something they attend, not something they live.

Fear of “forcing” tradition further complicates this dynamic. Mindful of their own experiences or eager to respect their children’s autonomy, parents hesitate to introduce culture at all. They worry that expectations will create resistance or resentment. While this concern is understandable, absence carries its own consequences. Children raised without exposure often grow up curious but disconnected, lacking the familiarity needed to engage confidently with their heritage later.

Over-assimilation is another subtle factor. Many immigrant parents equate success with seamless integration. Difference is minimized in the hope that children will belong more easily. Cultural distinctiveness is treated as optional, even inconvenient. Children absorb this message clearly: fitting in matters more than standing rooted.

This belief often goes unquestioned because its effects are not immediate. Children may thrive academically and socially while cultural connection weakens quietly. Only later—often in adolescence or adulthood—does the absence become noticeable, when young adults struggle to articulate identity, explain traditions, or feel comfortable in cultural spaces.

None of these patterns arise from neglect or indifference. They are the byproducts of noble intentions, shaped by a demanding environment. Yet recognizing them requires honesty.

Identity does not disappear suddenly. It fades when presence is replaced by efficiency, when culture is delegated rather than lived, and when silence replaces shared experience. Awareness is the first step toward restoration.

Reclaiming identity does not require rejecting American life or overwhelming children with tradition. It requires small, consistent acts of presence—bringing culture back into daily routines where it belongs.

Passing the Torch Without Burning the Bridge

The desire to preserve culture often carries an undercurrent of anxiety. Parents worry that if traditions are not actively protected, they will be lost. Yet culture passed through fear rarely survives. What endures is what is associated with joy, comfort, and belonging.

The desire to preserve culture often carries an undercurrent of anxiety. Parents worry that if traditions are not actively protected, they will be lost. Yet culture passed through fear rarely survives. What endures is what is associated with joy, comfort, and belonging.

Passing the torch does not mean tightening control or increasing expectations. It means creating an environment where culture feels welcoming rather than demanding. When children associate tradition with warmth and connection, they are far more likely to carry it forward voluntarily.

Invitation is far more powerful than enforcement. Children who feel compelled to perform rituals or conform to expectations often disengage emotionally, even if they comply outwardly. In contrast, when culture is offered as an invitation—to participate, to observe, to ask questions—it fosters genuine connection. Allowing children to step in at their own pace builds trust rather than resistance.

Letting children adapt traditions in ways that resonate with their lives is not cultural dilution; it is cultural continuity. Every generation reinterprets what it inherits. When children are allowed to personalize practices—celebrating festivals differently, blending languages, modifying rituals—they take ownership. Adaptation signals relevance, not loss.

Grandparents play a vital role in this process. They transmit culture without agenda, often through stories, memories, and lived examples. Their narratives connect children to family history and ancestral experience. Even when language barriers exist, emotional bonds communicate values that transcend words.

In families separated by distance, maintaining these relationships requires intention. Regular conversations, shared rituals across time zones, visits when possible, and storytelling preserve intergenerational continuity. Culture thrives when it is relational.

Family time, however brief, creates space for these exchanges. Storytelling during meals, casual conversations, and shared activities—all provide opportunities for cultural transmission without formal structure.

Passing the torch gently ensures it remains light enough to carry. When culture is offered with generosity rather than urgency, children receive it not as a burden, but as a gift.

Closing Reflection: What Endures

Culture does not survive through anxiety. It endures through love. When traditions are carried with fear—fear of loss, fear of change, fear of getting it wrong—they become heavy. Children sense this weight instinctively, and what feels heavy is often set down. What lasts is what feels welcoming, familiar, and alive.

The torch we speak of throughout this reflection does not need to be heavy to be meaningful. It does not require perfection, completeness, or constant vigilance. Culture survives not because every ritual is performed correctly, but because connection is sustained. A shared meal, a familiar prayer, a story told casually, a festival celebrated imperfectly—these moments accumulate quietly, forming a sense of belonging that does not announce itself but remains steady.

Even small acts matter more than we often realize. A child may not remember every explanation, but they remember how it felt to sit at the table together, to hear a grandparent’s voice, and to participate in a celebration that felt joyful rather than obligatory. These experiences leave emotional imprints that resurface later in life, often when least expected.

There is reason for quiet optimism. Culture is resilient when it is lived, not enforced. The next generation does not need to inherit tradition exactly as it was. They need to inherit the freedom to make it their own, grounded in familiarity and affection.

When we pass the torch gently—without urgency or fear—we allow it to illuminate rather than burden. And in doing so, we ensure that what truly endures is not just tradition, but belonging.

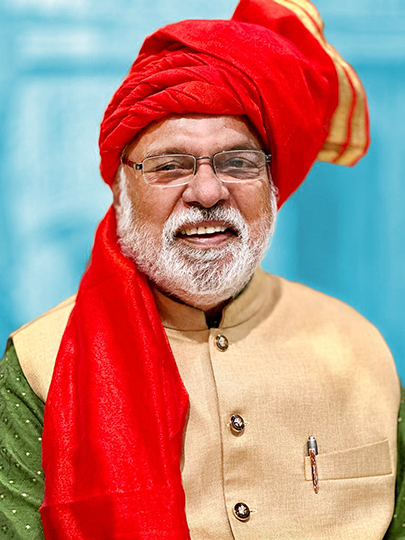

About the Author:

Raj Shah Software by profession, Indian culture enthusiast, ardent promoter of hinduism, and a cancer survivor, Raj Shah is a managing editor of Desh-Videsh Magazine and co-founder of Desh Videsh Media Group. Promoting the rich culture and heritage of India and Hinduism has been his motto ever since he arrived in the US in 1969.

Raj Shah Software by profession, Indian culture enthusiast, ardent promoter of hinduism, and a cancer survivor, Raj Shah is a managing editor of Desh-Videsh Magazine and co-founder of Desh Videsh Media Group. Promoting the rich culture and heritage of India and Hinduism has been his motto ever since he arrived in the US in 1969.

He has been instrumental in starting and promoting several community organizations such as the Indian Religious and Cultural Center and International Hindu University. Raj has written two books on Hinduism titled Chronology of Hinduism and Understanding Hinduism. He has also written several children books focusing on Hindu culture and religion.