Stagecoach to Pretoria: A Workshop in Gandhi’s Method of Nonviolent Resistance

|

| Stagecoach to Pretoria: A Workshop in Gandhi’s Method of Nonviolent Resistance By Doug McGetchin |

|

|

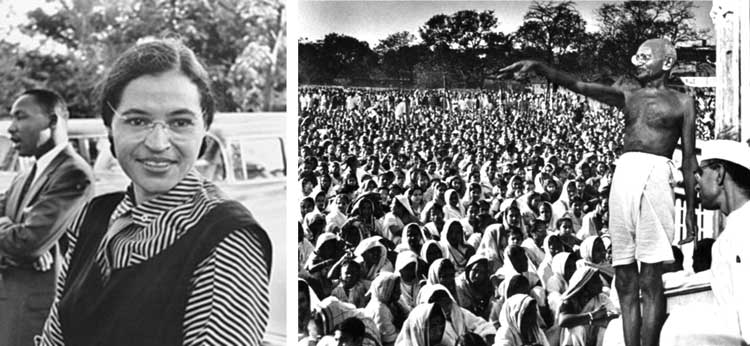

Another altercation a little later on the same journey on a stagecoach did not make the film and has remained largely unnoticed, but it is a striking reminder of how the power of nonviolent resistance works. The leader in charge of the stagecoach refused to let Gandhi sit inside the carriage with him and the other passengers, insisting instead the Indian visitor sit on top with the African driver, enforcing a racial divide. Gandhi initially decided to keep his mouth shut and obeyed. When they reached a rest stop, however, the leader wanted to get some fresh air on top of the coach. The man ordered Gandhi to move from his seat to make room. Gandhi had enough, like Rosa Parks who also refused to give up her seat on a segregated bus in Alabama, USA, over a half century later. Gandhi’s quiet determination echoed the parallel triggering incident in 1956 that started the Montgomery bus boycott, leading to a sustained struggle for civil rights that resulted in a significant victory using nonviolence in North America. Gandhi refused to budge, saying “I will not…but I am prepared to sit inside.” The bully became angry, using physical force to slap Gandhi around, trying to get his seat: “the man came down upon me and began heavily to box my ears. He seized me by the arm and tried to drag me down.” But Gandhi held on to his seat.

Nonviolence involves striving for a golden mean between the extremes of utter passivity and violent engagement. Gandhi could have given up his seat, or perhaps fought off the man. But by lowering himself to the physically abusive level of the bully, Gandhi would have been giving up the moral high ground. Gandhi was in the right, and by not fighting back physically, and yet also not yielding to the coercive demands of the leader, Gandhi was holding fast to the coach and his principles.

Taking the nonviolent stand he did took tremendous courage and creativity. Having dared to defy the fabric of white supremacy, Gandhi understandably feared for his life, as for the rest of the journey, the man eyed Gandhi angrily, pointed his finger, and threatened him with reprisal once they reached the next town. Gandhi wrote, “My heart was beating fast within my breast, and I was wondering whether I should ever reach my destination alive.” But the coach arrived at the town of Standarton and the Indian friends who were awaiting him there. The reprisal Gandhi feared never materialized. He even wrote a letter of complaint to the coach company and was able to travel the next day inside the coach, and the bully who had harassed him was not there. This scene the filmmakers of Gandhi pass over and Gandhi himself describes in his autobiography and yet does not emphasize enough the significance of this scene as a concise illustration of the power of nonviolent resistance. Although the bully was the leader of the coach, he was still dependent on the goodwill of the passengers. They had paid for their passage and were racial elites in that society, equal in social standing to the leader, and thus had influence over him.

Gandhi’s taking a principled stand got the attention of these crucial bystanders and won them to his side, undermining the bully’s pillars of support. Understanding this dynamic would be a consistent pattern in Gandhi’s struggle for justice and freedom throughout his fight for independence against the British. He realized it by not giving up his seat on a stagecoach on a dusty road to Pretoria in 1893. |

|

|

Doug Mc Getchin, Ph.D., Associate Professor, Depart-ment of History specializes in the history of connections between modern Europe and South Asia. He is the author of Indology, Indomania, Oriental-ism: Ancient India’s Rebirth in Modern Germany (2009) and several edited volumes. His his-tory courses include world, Germany, India, Gandhi, WW2, and Peace Studies. He is the Associate Director of the FAU Peace, Justice, and Human Rights (PJHR) Initiative for the Jupiter campus and holds the Osher Lifelong Learning Insti-tute Professorship in Arts and Humanities, 2018-19 |

|

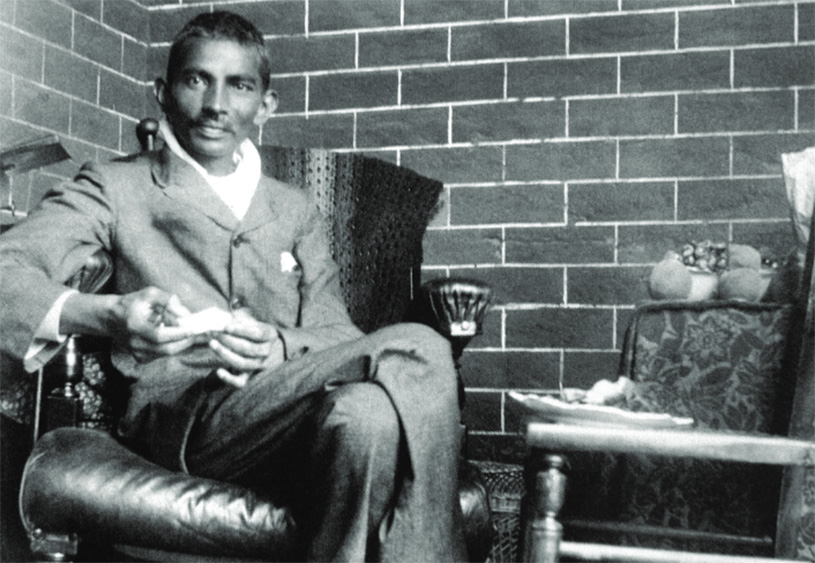

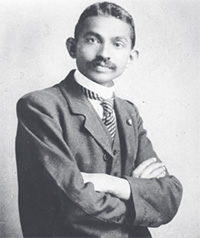

The young attorney Mahatma Gandhi’s first trip inland to Pretoria, South Africa, in 1893 by train and stagecoach was a highly symbolic journey, illustrating his resolve and the power of his methods of nonviolence. When Gandhi arrived in Durban, South Africa, he had a First Class ticket, but the racist South African conductor threw him from the train at night at Pietermaritzburg for daring to cross the color barrier. This famous scene appeared in the Oscar-winning 1981 Gandhi film, for good reason, as it fueled his passion for justice, an important step on the road towards becoming a leader of the In dian independence movement.

The young attorney Mahatma Gandhi’s first trip inland to Pretoria, South Africa, in 1893 by train and stagecoach was a highly symbolic journey, illustrating his resolve and the power of his methods of nonviolence. When Gandhi arrived in Durban, South Africa, he had a First Class ticket, but the racist South African conductor threw him from the train at night at Pietermaritzburg for daring to cross the color barrier. This famous scene appeared in the Oscar-winning 1981 Gandhi film, for good reason, as it fueled his passion for justice, an important step on the road towards becoming a leader of the In dian independence movement. At that point, Gandhi was manifesting the power of nonviolence. Gandhi’s courage and resolve in the face of an unwarranted physical assault aroused the sympathy of the other passengers, who came to his defense. Gandhi wrote, “Some of the passengers were moved to pity and exclaimed: ‘Man, let him alone. Don’t beat him. He is not to blame. He is right. If he can’t stay there, let him come and sit with us.’” The active intervention by these third party witnesses had a decisive influence on the altercation, as the “somewhat crestfallen” man “stopped beating” Gandhi and instead took the seat of the African driver who chose not to defy the man. Gandhi had used nonviolence to awaken the conscience and compassion of the passengers, who then applied their social pressure, which in turn caused the man to relent.

At that point, Gandhi was manifesting the power of nonviolence. Gandhi’s courage and resolve in the face of an unwarranted physical assault aroused the sympathy of the other passengers, who came to his defense. Gandhi wrote, “Some of the passengers were moved to pity and exclaimed: ‘Man, let him alone. Don’t beat him. He is not to blame. He is right. If he can’t stay there, let him come and sit with us.’” The active intervention by these third party witnesses had a decisive influence on the altercation, as the “somewhat crestfallen” man “stopped beating” Gandhi and instead took the seat of the African driver who chose not to defy the man. Gandhi had used nonviolence to awaken the conscience and compassion of the passengers, who then applied their social pressure, which in turn caused the man to relent.

In a sense, nonviolent resistance is a performance art. The late Gene Sharp (1928-2018) of the Albert Einstein Institute in his book Waging Nonviolent Struggle calls the important role bystanders play the “pillars of support.” Any ruler needs backing, support, from a critical mass of society. If the ruler loses this support, if the pillars that hold up the ruler’s regime start to crumble, then a ruler’s position is weakened and they usually cave in, either giving concessions, compromises, or lose power completely. Gene Sharp has documented 198 techniques of nonviolent struggle. Many of these actions such as marches, protests, parades, picketing, and strikes, involve a third party audience.

In a sense, nonviolent resistance is a performance art. The late Gene Sharp (1928-2018) of the Albert Einstein Institute in his book Waging Nonviolent Struggle calls the important role bystanders play the “pillars of support.” Any ruler needs backing, support, from a critical mass of society. If the ruler loses this support, if the pillars that hold up the ruler’s regime start to crumble, then a ruler’s position is weakened and they usually cave in, either giving concessions, compromises, or lose power completely. Gene Sharp has documented 198 techniques of nonviolent struggle. Many of these actions such as marches, protests, parades, picketing, and strikes, involve a third party audience.